In the waves of change we find our true direction – Leading Attendance Together International Network for School Attendance Conference Matthew White PhD

We have come such a long way in understanding attendance problems and developing approaches. However, now more than ever, there is increasing demand on education authorities in Australia and around the world to engage young people who have become disengaged or even detached from education (Watterston and O'Connell, 2019). The long-established approach when schools have exhausted all efforts to get a young person back to school has been to turn to adversarial measures (e.g. pursuing legal action etc). In some cases these measures can provide leverage to engage parents. However, we know for a majority of young people and often families the attendance problem continues to develop, becoming intractable as it is not properly understood or addressed. The multifaceted nature of attendance problems is often beyond the resources of schools and even large education jurisdictions. This has been increasingly the case in Australia as education jurisdictions struggle to support young peoples’ ‘bounce back’ from the pandemic.

Whilst there is a deep and growing body of literature on clinical approaches towards school attendance problems, there is currently a gap in the literature examining systemic responses towards attendance. Specifically, how do we scale the evidence of what we know about supporting the attendance of young people across schools and education systems? How can we reframe our understanding of a problems causes and solutions to meet the essential needs of most in more efficient and accessible ways? Lastly, how do we achieve sustainable organisational culture change? Specifically, we investigated one education System’s efforts to embed a nuanced attendance multi- tiered system of support. In doing this we saw that disruptive innovation may be the vehicle to scale what we know about preventing and responding to attendance problems so that context specific implementation knowledge can be used as leverage within system wide organisational change.

This study was situated within the Catholic Education Diocese of Parramatta (CEDP) CEDP is a demographically diverse system of 80 schools educating approximately 43,000 students across Western Sydney. The System comprises of 58 primary schools, 22 secondary schools, 2 trade training centres and 2 high support needs learning centres.

We investigate this change through the theoretical frameworks of implementation science, disruptive innovation and organisational change. We found the need for a synchrony of all three paradigms in order for both innovative and incremental change to take hold and remain sustainable.

Our first lens was Implementation science - How do we scale the evidence of what we know about supporting the attendance of young people across schools and education systems?

A growing number of studies demonstrate the efficacy of early and sustained access to psycho-social and education supports for young people who present with school attendance problems. However, barriers along the pipeline from research, evidence-based practice to widespread access to supports for young people and their families (e.g. cost, availability, reluctance to seek help) inhibit large-scale inroads.

Implementation science focuses on understanding the processes and factors related to successful integration of evidence-based interventions within a specific context. This includes determining how to successfully transport core components of an intervention to the professional practice setting, how to adapt the intervention to the local context, and how to enhance readiness for successful implementation by addressing the culture and climate of an organization or community. Thus. Implementation science has the potential to offer a means by which education authorities can increase uptake and sustainability of evidence-based supports and services.

Our second lens was disruptive innovation - How can we reframe our understanding of a problems causes and solutions to meet the essential needs of most in more efficient and accessible ways?

The concept of disruptive innovation was first presented in the Harvard Business Review by Bower and Christensen in 1995. The model describes how changes to current ways of doing business by reframing our understanding of a problem’s causes and solutions can enable us to meet the essential needs of most consumers in more efficient and accessible ways. Disruptive innovations simplify existing services or products that are inaccessible or out of reach for the majority of consumers.

A brief review of literature on disruptive innovation in education draws scarce references beyond advances in instructional delivery through technology. This can be attributed to the nature of disruptive innovation. Disruptive innovation requires investment, time and space for experimentation and a high tolerance for uncertainty (Serdyukov, 2017).

The highly regulated nature of education and ridged economic structures that govern service provision inhibit investment in service that does not appear to directly contribute to student academic outcomes. Thus, advances in the provision of wellbeing supports for students have traditionally favoured sustaining innovation whereby resources are invested into existing processes to meet a barrier to student engagement. We find that investment of time and space in schools and education systems can fosters collaboration, deep understanding and addresses the nuances of each young person’s situation.

Our third lens was sustainable organisational culture change. How do we achieve sustainable organisational culture change?

Systems and schools, as organisations are faced with constant internal and external pressures (e.g. demographics, technology, labour markets and community expectations). Schools generally respond in one of three ways to these pressures.

(1) The System or schools, consciously or unconsciously, maintain the status quo.

(2) The school or system may respond through a program of planned organisational change. This mode of change is often characterised by a top- down approach, whereby the System and school leaders work from a change model and drive the change. How this change is actualised can be as superficial as staff being directed to apply the change, to as deep as a formal collaborative change process (Pierce, Gardner, and Dunham, 2002).

(3) The third response may be organic or cultural change. These changes are often described as bottom-up change. They can come about through advance in scientific understanding, ideology and belief systems (dialectical change models). Individuals may collectively make sense of the need to change (social cognition). change may occur naturally within organisations in response to environmental and organisational demands (cultural change) (Beycioglu & Kondakci 2021).

Purposeful organizational change attempts to move an organisation from its current state (known) to a desired future state (unknown). The literature offers many structured step by step models for planned organisational change (e.g. Lewin’s three-stage theory of change (1947), Kotter’s eight-step process of change (1996), Roger’s diffusion theory (2003)). However, the models do not provide specific steps for how to achieve a desired outcome. The evidence both within industry and education points to the high failure rate of change initiatives. Therefore, change is sustainable when there is a shift in an organisations culture.

According to Fullan & Quinn (2015) in their text Coherence: the drivers of culture change in schools and systems come from: focusing direction, deepening learning, cultivating collaborative cultures, and securing accountability.

Statement of the problem

There continues to be a siloing of approach towards addressing school attendance problems. The heterogenous nature of attendance problems are often at odds with linear process required of schools to identify and respond to attendance concerns. Schools in Australia and many other countries are governed by legislative frameworks and procedures to ensure they identify attendance concerns, communicate those concerns to parents and apply increasing adversarial pressure on parents if the concern is not addressed. However, when an attendance concern manifests from purely a concern into a psycho-social issue the breadth of tools to understand and address the issue within an education system is often limited.

In contrast, the clinical and allied health approach to school attendance problems have been to seek to categorise the psychological cause and function of the problem for the individual. Whilst inroads can be made to understand the problem, the systemic factors maintaining the problem (e.g. family disfunction, poverty, bullying, inappropriate adjustments for disability) continue to present barriers to the young person returning to school. Thus, a synchronising of systemic and analytic approaches is needed.

An outcome of the siloing of wellbeing provision for young people has resulted in education systems reticence to invest in services that do not directly contribute towards the provision of academic outcomes for students. Should a young person in Australia develop an attendance problem, the legislation requires schools to triage the problem and places responsibility on parents to source and maintain access allied health support for their child (sometimes with support from school). However, studies suggest that families of young people who present with attendance problems are often those that have barriers or are reluctant to accessing social and /or allied health supports.

Methodology

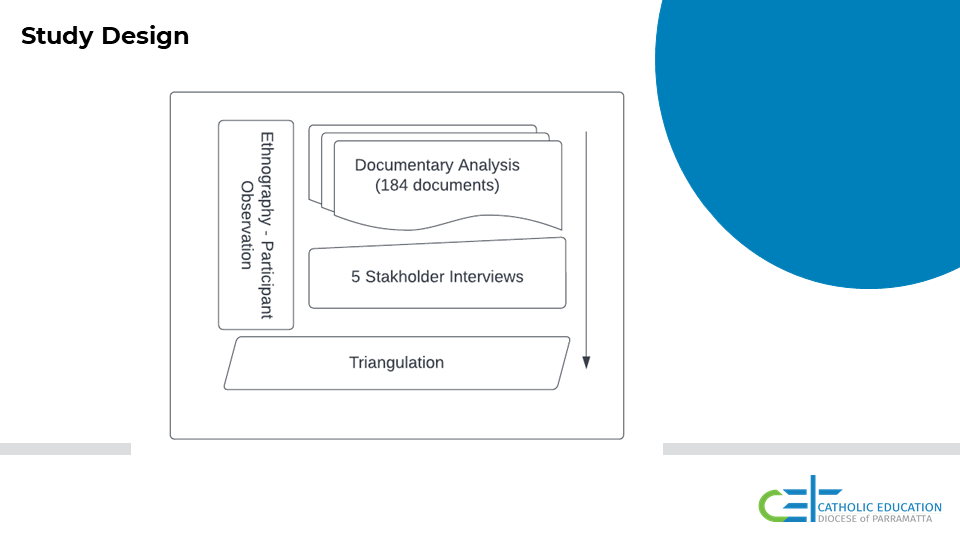

An exploratory case study approach was employed to investigate the effectiveness of the Attendance Team in achieving sustainable organisational change through the embedding of a multi- tiered system of support for student attendance. Documents and interviews were analysed through a constant comparison analysis approach. Through constant comparison analysis the researcher quantifies and codes the use of particular words, phrases and concepts to develop theory (O’Leary, 2014).

Alongside the analysis of interview transcripts and documents the researcher as a relatively new member of the Attendance Team also took on the role of participant observer.

Results

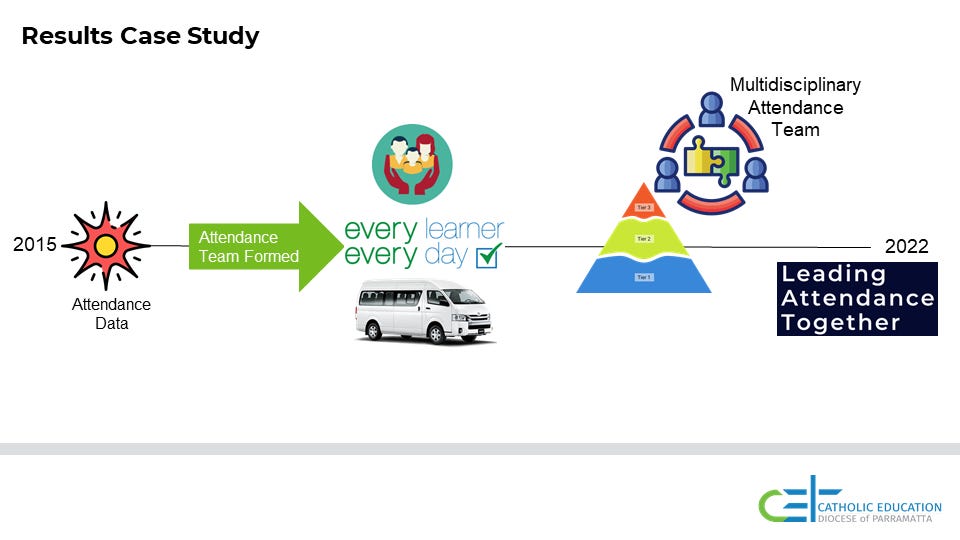

A recurring metaphor across the interviews and documentary analysis was attendance data representing the catalyst or “big bang” creating the sense of urgency for change in 2015. As described by the Attendance Manager –

“it presented the pernicious nature of school attendance problems. It is a problem hidden in plain sight. For school leaders it was the realisation of the scale and scope of the problem”.

The response to the data also highlighted the differing perspectives and drivers of action. From a wellbeing perspective it was viewed as an issue of injustice in the form of disenfranchisement of a large body of the student population from education. However, from a learning perspective the driver was the visible impact of attendance on academic and intervention outcomes. For example, the Head of Student Services outlined:

We were doing work with Lyn Sharrett putting faces on the data and examining the effect of our early years’ literacy interventions. We found despite out success there was still a group of students not succeeding. When we examined more closely, we found that the students were not succeeding because whilst it was recorded, they would receive twenty session they were not getting this as they were not at school.

There is evidence to point that the organisation was very forward thinking and ahead of many education authorities in Australia. Instead of maintaining the status quo or increasing pressure on schools, the System commissioned an investigation. This had two parts:

Understanding the problem, consultation with schools and synthesising findings for directors’ response.

Development of attendance support systems and procedure’s goal of separating therapeutic and legal response to absenteeism.

At the same time funding was provided for a school principal to undertake a sabbatical with the goal of investigating worldwide response to absenteeism. The principal visited Ireland, UK, Canada and USA. The key finding reported were that (a) the problem was universal and (b) at the core of addressing the problem was developing relationships. For example, the principal observed effective work was being undertaken in New Jersey reaching out to children in the year before starting school.

The Executive Director when interviewed elicited that the investment in attendance and wellbeing was an example of the organisations parting with convention and placing people at the centre of decision making in place of arbitrary perceived functions of an organisation. He stated:

Most organisations follow a form, function framework approach to decision making in contrast our approach has been people, purpose and process.

In 2016 the Attendance Team was formed. The forming of a team afforded time and space to develop attendance support systems and the beginnings of an in-house therapeutic response to school attendance problems. Evidence of disruptive innovation at this point can be seen through the conceptualisation of generating disruptive power. Disruptive power was described as:

We must seek first to understand the problem and why absences occur, who the students are, what the patterns are and what the barriers are to responding effectively…. Next it is disrupting the status quo and maintaining the disruption long enough to change the dynamic of business as usual. Key strategies that provided disruptive power were consistent and well understood processes; positive engagement and transparent use of data, universal and foundational expectation that coming to school regularly is critical to student achievement and wellbeing.

The Director of Wellbeing in response to his observation of the organisations disruptive innovation approach outlined that:

The causal influences that prevent a young person from going to school are often multi-layered and we know that there is not going to be a single solution. We can say to a young person that the law says you need to go to school but that is not going to get them out of bed. Therefore, the disruptive innovation we put in place is trying to provide a creative response to a wicked problem.

The embedding of a multi- tiered system of support across the System required concurrent activity from both the top down and also bottom up. Disruptive power was generated from the bottom up through developing shared understanding regarding attendance support processes (e.g. identifying attendance problems), deepening learning (building capacity of schools to hold effective attendance planning meetings) and fostering a collaborative culture across the system. From the top down there was a sharpening of systemic response towards attendance problems through a multidisciplinary (teachers, counsellors, social workers) approach. At the middle of the structure initiatives such as the Attendance Family Liaison program and the up and go bus provided effective measures in preventing and responding to attendance concerns.

It is evident that laying the foundations for a sound MTSS required time, space, resourcing and active sponsorship from System executive leaders. This was seen in the bringing together of System leaders in both 2017 and 2018 with the purpose of establishing a shared vision of Every Student Every Day across the System. Establishing a clear vision was identified as a core catalyst in changing the organisational culture regarding attendance.

A culture of attendance is best described as the way a whole school community thinks and acts regarding attendance. It moves beyond attendance as only an administrative and compliance task to attendance as a student-centred framework.

A culture of attendance also means a mindset where schools, school leaders and teachers believe they have agency, can make a difference with attendance and see absenteeism as a matter of urgency.

Whilst there were large scale efforts and investment at a system level to drive change the real sustainable change came from fostering a collaborative culture and deepening learning through relationships. As the Attendance Manager stated –

For me it is joining with schools. Having an attendance Team means we have an opportunity to join with complex systems to understand and define the problems and constraints they have at play and then to work with them to do what is needed.

The Primary Attendance Liaison leader, a retired principal supported the importance of relationship both when working with families and schools.

What I started to do was just look at the data and go and visit families of schools that were struggling most. I must have visited 100 families in my first year.

In describing her approach to work with schools:

I always say you do it how it suites you. …I don’t mind how you do it but these are the things we need to do. Sometimes they might change the structures after asking what should we do here? Gradually they have actually all come around to doing it much the same way by just by chatting to them and bringing them together.

The Director of Wellbeing also supported that relationship between those championing the change and school leaders was essential in achieving sustainable organisational cultural change:

The relationship between the organisational specialists championing the change and the school leaders, particularly the middle leaders is so important because knowing the community that you are working in you also know where they are on that journey and therefore can tailor that message so that you can challenge beliefs, practices and even share case studies if necessary.

My own participant observation has been that whilst systems may develop sound support processes and structures there is not one solution or end point. Instead Systems must continually review and remain agile to provide creative response to often wicked problems. As detailed by the Attendance Manager

There is no complete solution, so it is an evolution more than it is a one-way change process. We never have the full understanding and that is what complex problems present us with, there are so many factors at play

Discussion

1. Disruptive innovation provides a creative response to a wicked problem. It affords an open ended and individualised problem-solving approach.

2. The current MTSS framework offers a broader, more accessible, deeper and intensive support than was present in 2015. An assessment reveals the building blocks of an MTSS are in place (processes, systems and supports). However, there is still work to embed a common understanding of MTSS and establish MTSS processes across all schools.

3. Change management is a journey. Sustainable change is not a one-off event. Progress takes time therefore needs to be measured through examining the journey and the narrative of the participants.

4. Whilst efforts were made to drive change from the top the sustainable change has come from the symbiotic relationship between the Attendance Team and schools. We can’t understand organisation culture until we walk alongside schools in the journey.

5. For sustainable change in schools and systems there is a need for time and space to answer the questions that arise from implementation science and disruptive innovation. Planned organisational change is not enough to drive culture change. Systems may provide space and resources yet secure accountability through operating within clear frameworks.

6. It is essential Systems and schools have access to up-to-date attendance data to uncover the pernicious nature of attendance problems. It is a problem sitting in plain sight only visible through the constant collection and analysis of data. Evidence suggests there is now a greater focus on data analysis and data-based decision-making processes evidenced by the exponential increase in the number of referrals.